The following is an excerpt from John Medina's new book, "Brain Rules." You can also listen to the excerpt.

Above is a clip from the Brain Rules DVD about multitasking.

Multitasking, when it comes to paying attention, is a myth. The brain naturally focuses on concepts sequentially, one at a time. At first that might sound confusing; at one level the brain does multitask. You can walk and talk at the same time. Your brain controls your heartbeat while you read a book. Pianists can play a piece with left hand and right hand simultaneously. Surely this is multitasking. But I am talking about the brain’s ability to pay attention. It is the resource you forcibly deploy while trying to listen to a boring lecture at school. It is the activity that collapses as your brain wanders during a tedious presentation at work. This attentional ability is not capable of multitasking.

Recently, I agreed to help the high-school son of a friend of mine with some homework, and I don’t think I will ever forget the experience. Eric had been working for about a half-hour on his laptop when I was ushered to his room. An iPod was dangling from his neck, the earbuds cranking out Tom Petty, Bob Dylan, and Green Day as his left hand reflexively tapped the backbeat. The laptop had at least 11 windows open, including two IM screens carrying simultaneous conversations with MySpace friends. Another window was busy downloading an image from Google. The window behind it had the results of some graphic he was altering for MySpace friend No. 2, and the one behind that held an old Pong game paused mid-ping.

Buried in the middle of this activity was a word-processing program holding the contents of the paper for which I was to provide assistance. “The music helps me concentrate,” Eric declared, taking a call on his cell phone. “I normally do everything at school, but I’m stuck. Thanks for coming.” Stuck indeed. Eric would make progress on a sentence or two, then tap out a MySpace message, then see if the download was finished, then return to his paper. Clearly, Eric wasn’t concentrating on his paper. Sound like someone you know?

To put it bluntly, research shows that we can’t multitask. We are biologically incapable of processing attention-rich inputs simultaneously. Eric and the rest of us must jump from one thing to the next. To understand this remarkable conclusion, we must delve a little deeper into the third of Posner’s trinity: the Executive Network. Let’s look at what Eric’s Executive Network is doing as he works on his paper and then gets interrupted by a “You’ve got mail!” prompt from his girlfriend, Emily.

step 1: shift alert

To write the paper from a cold start, blood quickly rushes to the anterior prefrontal cortex in Eric’s head. This area of the brain, part of the Executive Network, works just like a switchboard, alerting the brain that it’s about to shift attention.

step 2: rule activation for task #1

Embedded in the alert is a two-part message, electricity sent crackling throughout Eric’s brain. The first part is a search query to find the neurons capable of executing the paper-writing task. The second part encodes a command that will rouse the neurons, once discovered. This process is called “rule activation,” and it takes several tenths of a second to accomplish. Eric begins to write his paper.

step 3: disengagement

While he’s typing, Eric’s sensory systems picks up the email alert from his girlfriend. Because the rules for writing a paper are different from the rules for writing to Emily, Eric’s brain must disengage from the paper-writing rules before he can respond. This occurs. The switchboard is consulted, alerting the brain that another shift in attention is about to happen.

step 4: rule activation for task #2

Another two-part message seeking the rule-activation protocols for emailing Emily is now deployed. As before, the first is a command to find the writing-Emily rules, and the second is the activation command. Now Eric can pour his heart out to his sweetheart. As before, it takes several tenths of a second simply to perform the switch.

Incredibly, these four steps must occur in sequence every time Eric switches from one task to another. It is time-consuming. And it is sequential. That’s why we can’t multitask. That’s why people find themselves losing track of previous progress and needing to “start over,” perhaps muttering things like “Now where was I?” each time they switch tasks. The best you can say is that people who appear to be good at multitasking actually have good working memories, capable of paying attention to several inputs one at a time.

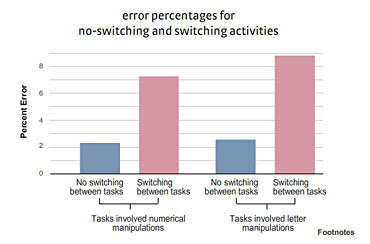

Here’s why this matters: Studies show that a person who is interrupted takes 50 percent longer to accomplish a task. Not only that, he or she makes up to 50 percent more errors.

Source: Rogers RD & Monsell, S (1995) Depth of processing and the retention of words in episodic memory Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 124(2): 207 - 231 Table 2 of Experiment Cluster #1 (crosstalk conditions)

Source: Rogers RD & Monsell, S (1995) Depth of processing and the retention of words in episodic memory Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 124(2): 207 - 231 Table 2 of Experiment Cluster #1 (crosstalk conditions)

Notes: These trials involved uninterrupted (single-focus) tasks and interrupted (multiple-focus) tasks. Data are shown for experiments involving number-based manipulations and letter-based manipulations.

Some people, particularly younger people, are more adept at task-switching. If a person is familiar with the tasks, the completion time and errors are much less than if the tasks are unfamiliar. Still, taking your sequential brain into a multitasking environment can be like trying to put your right foot into your left shoe.

A good example is driving while talking on a cell phone. Until researchers started measuring the effects of cell-phone distractions under controlled conditions, nobody had any idea how profoundly they can impair a driver. It’s like driving drunk. Recall that large fractions of a second are consumed every time the brain switches tasks. Cell-phone talkers are a half-second slower to hit the brakes in emergencies, slower to return to normal speed after an emergency, and more wild in their “following distance” behind the vehicle in front of them. In a half-second, a driver going 70 mph travels 51 feet. Given that 80 percent of crashes happen within three seconds of some kind of driver distraction, increasing your amount of task-switching increases your risk of an accident. More than 50 percent of the visual cues spotted by attentive drivers are missed by cell-phone talkers. Not surprisingly, they get in more wrecks than anyone except very drunk drivers.

Watch the video below from the Brain Rules DVD.

It isn’t just talking on a cell phone. It’s putting on makeup, eating, rubber-necking at an accident. One study showed that simply reaching for an object while driving a car multiplies the risk of a crash or near-crash by nine times. Given what we know about the attention capacity of the human brain, these data are not surprising.

Do one thing at a time

The brain is a sequential processor, unable to pay attention to two things at the same time. Businesses and schools praise multitasking, but research clearly shows that it reduces productivity and increases mistakes. Try creating an interruption-free zone during the day—turn off your e-mail, phone, IM program, or BlackBerry—and see whether you get more done."

12 comments:

Long before the cell phone, cars were equipped with seats for non-drivers. Is there any difference in attention and switching costs for conversations with physical passengers as compared to cell phone passengers?

How is that I can drive and listen to the radio at the same time? I don't crash and I can remember what I was listening to (even talk radio) a short while later.

What is strange is that when I use a handsfree for my cell/mobile phone I seem to be able to drive better than when I have no handsfree. I don't pay attention to the caller very well with a handsfree, though.

In a tragic accident near here last winter, a car plunged into a pond and drowned five teenagers. Research shows that even two teenagers in a car doubles the crash risk.

I don't know this, but maybe when people are in a car, they can also sense the tense situations, and eihter shut up, or even (when driver adults)help. Small children excepted. Maybe that is why they now have to be in the back seat in some states.

Relative to Allen's point, the brain can do some multitasking better than others. It actually can multitask (vs. task switch) outside of consiousness. So, you may not be able to walk and chew gum, but I bet you can walk and talk at the same time.

Do you, like most people, turn down the radio when looking for a street name or address?

Even with the confines of a particular task, there are multiple tasks that have to be accomplished whether driving( gear shifts, looking in rear vision mirror) or different work situations. Even when we are talking multiple areas of the brain are active. If we can correlate that many areas of the brain are active for talking then you could use the arguement/analogy that the brain is designed to multitask;it just depends on your goal.

This message should be posted in every business, every school; it should be taught to the young and to the old, put in drivers ed manuals, etc...

I have seen time and time again people being distracted by using thier cell phones - in driving - the person swerving while they drive, who veries wildly in thier speed and pays no attention to other drivers; and I have seen people talking on thier cell phones while walking run into things - telephone poles, other people, doors, etc.

@bfernald: If you ever happen to read this, I read not that long ago that non-drivers were also helpful to the driver when unexpected events arrive, whereas cell phone callers do not see and perceive the driver's environment. Have you never said to a driver "caution, this car..." just before the driver corrects his way while driving as a passenger ?

@Oct: You get right to my point. When a passenger says "look out" the driver either continues giving attention to the road, or gives their attention to the passenger. So, cell phones and passengers may cause equal distraction, and cell phones give you the added benefit of being able to turn them off.

okay, Im a student and doing an expiriment about reaction time

i test them first with there full attention and get them to play this game, then i tested them again with the same game but me asking them complex questions all my results came up that when i ask them they have quicker reaction time than fully focasing on the game?

Human brain can multitask but is limited. Our brain can do 2 or 3 things at the same time.

I have seen time and time again people being distracted by using thier cell phones - in driving - the person swerving while they drive

A nonny mouse wrote on December 28, 2008 4:53 PM

"I have seen time and time again people being distracted by using thier cell phones - in driving - the person swerving while they drive, who veries wildly in thier speed and pays no attention to other drivers; and I have seen people talking on thier cell phones while walking run into things - telephone poles, other people, doors, etc. "

And the above clearly typed by a person multitasking :-

An iPod dangling from their neck, the earbuds cranking out Tom Petty, Bob Dylan and Tatu as their left hand reflexively tapped the backbeat. The laptop had at least 11 windows open, including two IM screens carrying simultaneous conversations with MySpace friends. Another window was busy downloading an image from Google. The window behind it had the results of some graphic they were altering for MySpace friend No. 2, and the one behind that held an old Pong game paused mid-ping.

Post a Comment